Introduction

“I must go and have a bath. Yes, it’s time,” writes a Roman schoolboy in his exercise book almost 1800 years ago. “I leave; I get myself some towels and follow my servant. I run and catch up with the others who are going to the baths and I say to them one and all, ‘How are you? Have a good bath! Have a good supper!’” (Yegul, 30) Such was the accepted universality of bathing as a daily event in the lives of all Romans - young or old, and regardless of one’s sex, race, religion, or wealth, all were invited and expected to have a “bene lava,” a good bath. Visiting one of many public bathhouses was the norm, as no extensive bathing facilities existed in most Roman dwellings. Imperial thermae were the grandest of the public baths. The high level of expertise needed for their construction and the expense of the luxurious décor within meant that oftentimes only the emperor had the resources to commission them. Small privately owned baths called balneae were more common, but fell far short of the thermae in terms of facilities, opulence, and scale.

In fact, the Baths of Caracalla, one of the most famous thermae, was second only to the Colosseum in terms of large scale building projects (Menen, 92). As evidenced by their size alone, they did much more than fulfill a basic hygienic necessity. They served as community centers, providing all the facilities needed for the ideal urban life – a highly desirable balance between physical health and intellectual well-being. One could find gyms, shops, gardens, libraries and lecture halls at the baths. Since entrance fees were often partially or completely subsidized by the government or wealthy individuals, common people could enjoy the available recreation, education, and entertainment. To them, the baths were so important that, according to Yegul, “among the most effective punishments that could be imposed by the government on a community was the closing down of its baths for a period of time” (Yegul 30). Indeed, a daily habit was transformed into a civic institution and eventually became an essential part of Roman identity. It would have been un-Roman not to bathe (Yegul, 2).

Caracalla

Caracalla (186 – 217 CE), an emperor of the Severan dynasty, also recognized the importance of the baths, but for a different reason. The construction of lavish thermae was an immense public work, and it was a given that popular support of the emperor would skyrocket upon its completion. They were richly adorned with trophies, inscriptions, and sculptures, all constant reminders of the prosperity and peace brought by the emperor to the mighty empire. As sources of pride for the community, thermae-building could bestow a lot of power on those who dared to undertake it. It was therefore a useful propaganda tool for an emperor who desired a means to a political end – for example, to bring himself honor and esteem, or to ensure the outcome of an election (Raaschou-Nielsen, 149). Hoping to establish a lasting legacy and increase his popularity with the Roman people, Caracalla insisted on building his namesake baths at all costs. He was an unpopular military dictator who developed a reputation early on for being psychotic and bloodthirsty. There are accounts of Caracalla’s many quirks stemming from his obsessive desire to resemble Alexander the Great. For instance, he would always walk with his head tilted to the right, to emulate Alexander’s pose in famous works of art (Piranomonte, 51). He was also prone to bouts of “mad logic,” as demonstrated by Menen in an excerpt from one of Caracalla’s dialogues: “It is clear that if you make me no request, you do not trust me, if you do not trust me, you suspect me, if you suspect me, you fear me, if you fear me, you hate me. Off with his head…” (Menen, 150) Whether one had a request or lack thereof did not matter when Caracalla craved violent severity; he was a dangerous man. Originally, Caracalla’s father Septimius Severus, the first of the Severan emperors, had planned for Caracalla to rule the empire jointly with his brother Geta and his mother Iulia Domna. Caracalla had other plans. He murdered Geta in 212 and, with the purchased support of the army, left more than a thousand Romans dead in the process of securing his emperorship. It is no wonder that he needed the thermae to give his reputation a boost.

Bust of Emperor Caracalla. Rome, Roman National Museum, Palazzo Massimo at the Baths (Piranomonte, 51)

Septimius Severus began building the baths during his reign, and had left his son a full treasury to continue construction. But the project proved so expensive that Caracalla resorted to extorting the necessary money from wealthy senators. He became popular among the poor, however, who now had a wonderful community center offering all the best pleasures of Roman urban life.

So attractive were these pleasures that baths tell the story of Romanization and urbanization throughout the empire; in fact, the empire’s extent could be indicated by the presence of balneae and thermae. The bathing custom was an effective tool for assimilating conquered peoples into a single, standard culture. Even with its many differences and similarities, the vast imperial Roman civilization could be unified by a coherent pattern of practices that featured bathing’s universal prevalence as its mainstay. It was an activity with the potential to involve the entire urban population and was not confined to the elite like many other Roman pastimes (Raaschou-Nielsen, 149).

History and Origins of Bathing

The act of bathing itself was not a uniquely Roman hobby. As is common with many facets of the ancient Roman world, they borrowed practices from other cultures. In this case, the Romans developed the Greek custom of bathing daily in small private balneae (Menen, 191). Thus, the first baths in Italy were small domestic balneae meant to provide a “good sweat,” a folk remedy for seasonal ailments (Yegul, 50). It is in these balneae that the three basic elements of a Roman bath are first seen: a caldarium (hot room), a tepidarium (warm room), and a frigidarium (cold room). They were privately owned and small, often sharing their walls with surrounding buildings. Though most were open to the public, a potent combination of increasing public interest in bathing and a strong prospering economy led to the construction of thermae, which replaced old and disused balneae. In contrast to the balneae, thermae were huge freestanding structures almost always owned by the state or city and could cater to hundreds of bathers at once (Yegul, 43).

Demand for bathing facilities was at an all-time high. Where people had normally taken a bath about once every ninth day, by the time of Commodus in the late 100’s every Roman bathed once a day, if not more – Commodus himself is said to have to taken a bath 7 to 8 times a day (Raaschou-Nielsen, 137). Bathing truly became a way of life, and Romans were in love with it. A highly sensational and enjoyable experience, to bathe was to soak in a warm clear pool for hours, muscles still tingling from a soothing massage, eyes dazzled by glittering treasures and smooth marble surfaces, while taking in the peaceful echoes of falling water and the aroma of sweet-smelling ointments and perfumes. It would awaken both body and mind. Furthermore, the shared, egalitarian experience of bathing with others was socially satisfying, It encouraged a “classless world of nudity that encouraged friendships and intimacy” (Yegul, 5), and often preceded dinner feasts full of social companionship and entertainment. Bathing had a special place in the structure of a Roman day, an irreplaceable part of a grand ritual of delightful luxury.

The Bath Ritual

The bath itself was highly ritualized. According to the poet Martial, the best time to bathe was 2 o’clock in the afternoon, after lunch and a short siesta. Since the Roman workday was confined to the morning hours, men would often stay at the baths for several hours, until dinner. If one’s schedule did not allow it that day, the bath could possibly be postponed, but under almost no circumstances should it ever be skipped. Still, bathing at night was not encouraged. Large windows provided most of the lighting, so most baths closed before dusk. Fuel was too costly to allow frequent use of artificial lights such as oil lamps. But even with the presence of artificial light, baths were large buildings with negligible security in place – they hid enough danger to make even the most courageous bather think twice about a nighttime excursion.

Most bathers arrived in the mid-afternoon, each carrying their own set of bath equipment. For the wealthy, it was a status symbol to be carried to the bathhouse on a sedan chair with a train of slaves bearing garments and implements in tow. This would include their exercise and bathing garments, sandals, linen towels, and a cylindrical metal box called a cista that stored oils, perfume, and sponges. As the Romans did not have soap, strigils were used for scraping oils off the skin after a massage and exercise.

Flasks of anointing oils and perfumes, the contents of a typical cista, are depicted on the left. The utensil on the right is a strigil, a curved metal blade for scraping excess oil from the body after bathing. This would also be stored in the cista when not in use. Naples Archaeological Museum (Yegul, 34).

Most people, however, carried their own equipment and could only afford one professional assistant to anoint and strigil them.

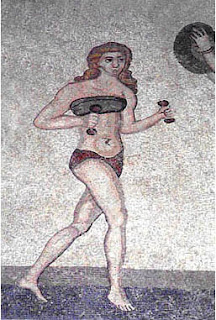

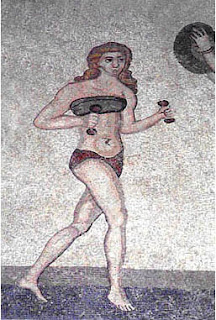

The first stop upon entering the baths would be the apodyterium, much like a modern-day locker room with shelves and cabinets to store clothing and personal effects. There were benches for slaves and servants to sit and keep watch over their masters’ belongings, as theft was quite common. The bather would undress here and move to one of many heated rooms for an oil massage before exercising in a courtyard called a palestra. The exercise was not meant to be strenuous; only athletes exercised vigorously. For ordinary people, working up a light sweat was enough to reap health benefits. Ball games were very popular with both men and women. Men favored running, wrestling, boxing and fencing, while it was more suitable for women to swim in the natatio (the swimming pool) or roll a metal hoop called a trochus with a stick.

Mosaic probably depicting a competition for women athletes, not ordinary practice. It was usually considered unacceptable for women to exercise with weights and dumbbells. Sicily, Piazza Armerina, 4th cent. (McManus)

The second-floor rooms above the palestra were most likely used for sunbathing, massage, or plucking unfashionable body hair. Professional hair-pluckers called depilators were available for hire in these rooms (Yegul, 33).

The tintinnabulum bell announced the opening of the hot baths, and when it rung, all activity in the palestrae would immediately cease. Excited bathers could either go to a sauna-like sweating chamber called the laconicum, get anointed with oil a second time, or soak in the warm tepidarium to start the bath in earnest. The general order of movement from room to room proceeded from the warm tepidarium to the hot caldarium. The bath ended with a plunge in the cold frigidarium. Of course, “one bathed as one wished” (Yegul, 39) and this was not a fixed routine.

Bathers tended to linger in the admirably illuminated caldarium and frigidarium, which were common meeting places for social gatherings and performances. Traveling entertainers such as jugglers and musicians were always present, as were vendors of food and wine. There was something for everyone here, whether it was the sensual dip in the pool and the possibility of getting a tan from the sunlight streaming through the sparkling windows and water, the merriment of eating and drinking with friends in the hot baths, or the peace of contemplative thought after a stirring oration at one of the lecture halls.

Reconstruction drawing of the frigidarium at the Baths of Caracalla, illustrating the building’s grandeur. Viollet le Duc, 1867 (Keller)

One could imagine the sounds emanating from the many different rooms of the baths and blending together in the large central frigidarium. Unfortunate enough to live next to a city bath, Seneca wrote a critical and satiric account of the deafening din:

“…panting and grunting hearties as they swing weights; the smacking noise of body massage; someone yelling out the scores of a ball game; and the commotion caused by a thief caught stealing. To these noises were added the singing of the man who likes his own voice under the vaulted halls; the enthusiast who splashes indelicately in the public pool; the shrill voice of the hair-plucker advertising his trade, or worse, the yelling of his victims; and the incessant cries of the cake-seller, the sausage-seller, the candyman, each with his peculiar tone and style…” (Yegul, 32)

Social Impact

When bathers finally began to leave around dinnertime, friends would say goodbye with “Salve lotus!” This can be translated as “I hope you have bathed well.” In ancient Rome, no one was barred from the all-important pursuit of bathing well; anyone who could afford a negligible entrance fee, usually no more than half a cent, could attend one of the eleven thermae or choose from more than eight hundred balneae in Rome that were open to the public. Subsidized by endowments, some were even free (Carcopino, 254).

Since bathing was such an affordable luxury for all, people from many different walks of life could mix freely. There is no evidence of any formal social segregation whatsoever occurring at the baths, and generally, bathhouses were not built specifically to serve any particular classes of clientele (Fagan, 206). The grand thermae of Rome were located to allow easy access from all areas of the city. Many Roman emperors enjoyed bathing with their subjects in the public baths, where they could rub shoulders with the lowliest laborer and gain popular support. This created the temporary illusion of a “classless society,” and as bath scholar Fagan suggests, public bathing was a social leveling system. Some argue that de facto social segregation still occurred, as the wealthy would bathe surrounded by a throng of slave attendants. In fact, during the height of the empire such idleness was considered fashionable, and it was chic to be “thought incapable of doing anything except to have sex and eat” (Menen, 197). It is interesting to note that this life of excess and leisure was made possible by the Roman economy’s dependence on slave labor.

However, the status of slaves at the baths is unknown. They definitely served as attendants while their masters bathed, but direct evidence as to whether they could actually use them as customers is in the form of scarce graffiti or inscriptions on the walls of certain bathhouses (Fagan, 200). It is possible that some slaves had the opportunity to bathe while on duty, but not all attendants would be so lucky – for example, the vigilant slaves who guarded their masters’ clothes in the apodyterium were flogged if they left their post.

Also, Roman medicine promoted bathing as a remedy for many illnesses. With an average life expectancy of 30 years, Romans lived short lives and fell ill often. Thus, as there were no separate facilities for medically prescribed bathing, the healthy and the sick often bathed together. This was another social leveler, albeit detrimental in terms of public health (Fagan, 85).

Integration by gender was not tolerated on the same level. Men and women usually bathed separately, and though some emperors tolerated mixed bathing, the women who visited heterosexual baths did not have the best reputations. More common was the practice of assigning different bathing times: women would bathe in the morning while men would bathe in the more desirable afternoon hours (Yegul, 33).

Bath Architecture and Technology: The Baths of Caracalla

A large part of the enjoyment associated with public bathing was due to the grand beauty of the bath building itself. To reiterate, the vast thermae of Caracalla was a massive treasury-draining construction effort. 9000 workers were employed daily for five years from 212 to 217, and they used several million bricks and more than 252 columns total. 16 of those columns were more than 12 meters high. The whole complex, including the gardens surrounding the central building, occupies a rectangular area of about 337x328 meters and could accommodate up to 1600 bathers at a time (Piranomonte, 13). An extensive network of underground passageways was used for maintenance and storage.

Plan of the Baths of Caracalla, with the main features labeled (Piranomonte, 16).

As can be seen from the figure of the plan, the central building was symmetrical. To accommodate the huge volume of customers, the Romans found it more effective to increase the number of rooms rather than their size. The number of entrances and passageways to a room, not its size, determined the flow of the crowd (Delaine, 45). Additionally, the main heated rooms – namely the tepidarium and caldarium – tended to be smaller and situated along the axis of the building, which expedited the heating process.

Solar heating was well-understood, so the caldarium windows were oriented towards the south to make the best use of the sun’s warmth. But that alone could not get the air hot enough, so the Romans developed the hypocaust system. Hypocaust means “fire underneath,” and literally, there were fires burning under the floor. Pillars called pilae raised the caldarium floor about three feet, and large tiles were laid on top of these pillars, to be covered with a layer of concrete and marble. An underground furnace provided the fire; the hot gases it created were drawn through the floor space, and heated the floor as they rose and spread out. A series of stacked clay tubes called tubuli lined the insides of the walls and created vertical channels for gases to rise through the walls. Apertures in the roof allowed gases to escape. Heat circulation could then continue and the air inside the caldarium would heat up.

Diagram of hypocaust system (Yegul, 358).

The hypocaust did not heat the water, which was still cold having traveled by aqueduct to the baths. Heating water for the heated pools - 7 hot pools in the caldarium and 2 warm pools in the tepidarium - was accomplished by lighting fires under metal boilers underground. It is not known exactly how hot the water was, but there are accounts of heavy drinkers being carried out unconscious (“Roman Bath”). To maintain these kinds of temperatures, up to 50 furnaces total would be burning at once, consuming an average of 10 tons of wood a day (Piranomonte, 15).

The lofty interior spaces of the central rooms owed their size to the Roman technique of vaulting, which made use of a complex combination of many arches to support the weight of the roof. Before vaulting, ancient builders such as the Greeks supported their roofs with a forest of columns. This greatly compromised the amount of interior space. The Roman solution to this was to build the roof in two curved halves, separately. The weight of a keystone dropped in at the top would push down and outwards on the sections, holding the roof together and freeing up space underneath ("Roman Bath").

Section of the frigidarium wall at the modern-day Baths of Caracalla, showing extensive vaulting. (Prins)

None of this would have been possible without the advent of waterproof concrete, arguably the most important technology the Romans developed. The starting material was limestone, cheap and readily available. Heating the stone drove off the carbon dioxide and turned limestone into quicklime. Quicklime was then soaked, or ‘slaked,’ in water to make lime. The Romans added sand and rocks to the lime putty, mixed in crushed tile for waterproofing and included volcanic ash if possible. The end product was a distinctive pink concrete, found in almost all Roman buildings ("Roman Bath").

More available space also meant more room for lavish decorations. Hundreds of bronze and painted marble statues stood in every niche, and the important halls featured fountains and extensive polychrome marble facing. Indeed, every available surface would either be painted or covered with a mosaic. Fragments of stucco decorations can still be seen, attached to the walls of the frigidarium.

Colored mosaic from the floor of the eastern palestra. Materials for the many mosaics in the baths came from all over the empire; for example, yellow marble was imported from Numidia, green-veined marble came from Carystus, and granite and porphyry came from Egypt. To bathers, this served as a constant reminder of Rome’s far-reaching influence and power. (Prins, “Floor Mosaic”)

Fragment of mosaic located on the terraces of the eastern palestra, depicting a cupid on a sea monster. (Prins, “Cupid”)

However, the original décor is all but completely missing. The Baths of Caracalla were abandoned in 537, after only three centuries of use. As if confirming the prominence of bathing as important part of Roman identity, the fall of the empire coincided with the demise of the baths. Invading Goths severed key aqueducts, cutting off the water supply to Rome. The baths were too far from the city center to be properly defended and were therefore abandoned. As early as the 12th century, they were quarried for building material to decorate churches and palaces (Piranomonte, 4). Four centuries later, the Farnese Pope Paul III excavated the baths for the purpose of decorating a new palazzo. The statues and precious objects that were being taken from the baths caused great interest among the public; due to increasing removal and relocation of artifacts, the site deteriorated quickly.

Conclusion

At first, how the Romans were able to spend half of one’s waking hours every day bathing seemed strange and impossible to me. The concept seemed less strange when considering the slave-driven economy, which allowed a life of leisure for most of the empire’s citizens. Whether slaves were allowed to bathe is still uncertain.

Given the scale and the relatively short time it took to build the bath, it can be inferred that a strong economy and construction industry was solidly in place during Caracalla’s reign. The Severan period is often considered the high point of Roman construction (Delaine, 10). Gone was the time of architectural uncertainty and experimentation. The hundreds of baths built prior to this period provided countless laboratories for attempting new construction methods, and out of this creative experimentation came the development of waterproof concrete, vaulted ceilings, and innovative heating technology.

Though much of the baths’ original grandeur has been stripped away, the impressive ruins still stand as a monument to the sophistication of ancient Roman architecture. The Basilica-like, granite-columned hall of the frigidarium alone has directly inspired the architecture of many subsequent structures. Buildings as recent as the Chicago Railroad Station are exact copies of bath architecture (Piranomonte, 24). Caracalla’s thermae is therefore an excellent case study; it showcased Roman achievement in architecture and artistic design, and utilized the best of the technology available.

Statue of Hercules found in the frigidarium of the Baths of Caracalla, It is often called the Farnese Hercules due to its recovery and subsequent acquisition by Alessandro Farnese in the 1540’s. Naples, National Archaeological Museum. (Piranomonte, 39)

The wonder and admiration surrounding the art at the baths still exists, but it is art uncredited; we cannot attribute the stunning statues – even the Farnese Hercules - to any one artist or school of artists at all. Instead, this indicates the high standard of art at the time; the skill that went into the creation of those works was nothing out of the ordinary. An army of tradesmen worked diligently to complete them, with wondrous skill that was unmatched until the time of the Renaissance. Even parts of the bathing ritual have survived to this day; the Turkish bath is a direct descendant of the Roman custom. As a “microcosm of many of the things that made life attractive” (Carcopino, 256), the universality of baths and bathing in Roman society are an ideal lens through which to study the lives of the ancients.

Bibliography

Carcopino, Jerome. Daily Life in Ancient Rome : The People and the City at the Height of the Empire. New Haven : Yale UP, 2003.

DeLaine, Janet and David E. Johnston, eds. Roman Baths and Bathing: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Roman Baths held at Bath, England 30 March - 4 April 1992 . Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 37. Dexter: Thomson-Shore, 1999.

Fagan, Garret G. Bathing in Public in the Roman World. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

Keller, Sven. “Caracalla Leduc.” Photo. Caracalla-Thermen. 16 Aug. 2007. <http://www.roma-antiqua.de/antikes_rom/circus_maximus/caracallathermen>

McManus, Barbara F. “Piazza Armerina gymnast.” Photo. Roman Baths. Jul. 2003. 16 Aug. 2007 <http://www.vroma.org/~bmcmanus/baths.html>

Menen, Aubrey. Cities in the Sand. New York: Dial Press, 1973.

Raaschou-Nielsen, Inge V. Thermae et Balnea : The Architecture and Cultural History of Roman Public Baths. Aarhus : Aarhus UP, 1990.

Roman Bath (Secrets of Lost Empires II). Prod. NOVA. Videocassette. WGBH Boston Video, 2000.

Piranomonte, Marina.The Baths of Caracalla. Guide Electa per la Soprintendenza archeologica di Roma. Milan: Electa, 1998.

Prins, Marco. "Cupid on sea monster." Photo. Livius Picture Archive: Rome - Baths of Caracalla. 16 Aug. 2007. <http://www.livius.org/a/italy/rome/baths_caracalla/baths_caracalla2.html>

---. "Floor mosaic." Photo. Livius Picture Archive: Rome - Baths of Caracalla. 16 Aug. 2007. <http://www.livius.org/a/italy/rome/baths_caracalla/baths_caracalla2.html>

---. "Frigidarium wall." Photo. Livius Picture Archive: Rome - Baths of Caracalla. 16 Aug. 2007. <http://www.livius.org/a/italy/rome/baths_caracalla/baths_caracalla1.html>

Yegul, Fikret. Baths and Bathing in Classical Antiquity. New York: MIT Press, 1992.